This document describes how to write OWL ontologies in Attempto Controlled English (ACE).

To begin, here are some simple statements that are usually found in ontologies. The ACE representation is contrasted with a "formal language" representation that is normally used in such ontologies. Our work intends to show that natural language, if carefully controlled, provides a more readable and writable ontology representation, without a loss in generality and expressive power.

| ACE | Formal language |

| Every man is a human. | man ⊆ human |

| Every human is a male or is a female. | human ⊆ male ∪ female |

| John is a student and Mary is a student. | {John, Mary} ⊆ student |

| No dog is a cat. | dog ⊆ ¬ cat |

| Every driver owns a car. | driver ⊆ ∃ own car |

| Everything that a goat eats is some grass. | goat ⊆ ∀ eat grass |

| John likes Mary. | <John, Mary> ∈ like |

| Everybody who loves somebody likes him/her. | love(X, Y) ⇒ like(X, Y) |

Not all ACE constructions map nicely to OWL. Therefore, we describe only a subset of ACE. This subset does not contain adjectives, adverbs and prepositional phrases; intransitive and ditransitive verbs; queries and imperative constructions; modality and sentence subordination; and negation as failure.

The following OWL constructions are currently not supported by the ACE-to-OWL mapping.

Note that some OWL elements will never be supported, because they are just syntactic sugar and have furthermore no clear ACE counterparts.

The following text is structured to separately discuss the three main building blocks of ontologies as used in OWL: individuals, classes and properties.

One can talk about individuals, classify them and describe relations between them. For example,

There is a man. The man is John. His age is 32 and he likes Mary. Mary loves herself. Bill sees something. John is not Bill.

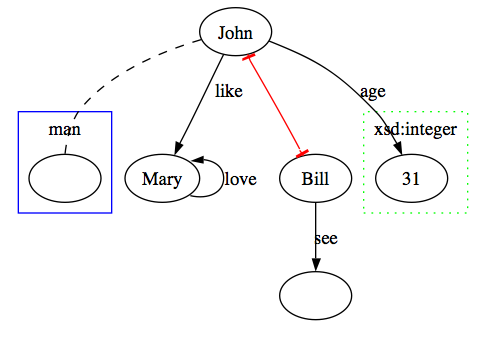

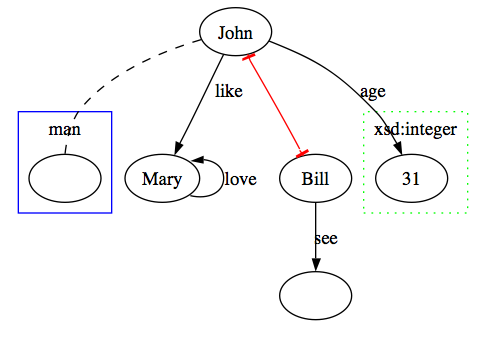

The following graph visualizes the model described by the story, with individuals (denoted by ellipses), their belonging to classes (boxes with labels), properties (solid arrows with labels), equality (dashed line) and difference (red line). Data-values are in a box with dotted border. In case the name of an individual is know then it is written into the ellips.

OWL does not make a unique name assumption, i.e. an individual can have different names and one has to explicitly state the equivalence or difference of two differently named individuals. Therefore, whether Mary is John or is Bill or is different from both of them, is still open, we only know that John is not Bill. The fact that John belongs to the class man is not explicit in the picture, but can be derived by simple reasoning. Note also that John, Mary, Bill and the thing that Bill sees, all belong to the topmost class owl:Thing.

One can also classify the individuals by complex class descriptions, e.g.

One can describe classes by specifying relations to other classes. Such relations can be a simple inheritance from a named class ("Every man is a human.") or more complex property restrictions ("Every driver owns a car."). In OWL, the classes do not need names, they can be abstract descriptions, e.g. "(Every) man who owns a dog ...". Such descriptions can be made arbitrarily complex by negation (no, is not, does not), disjunction (or, or that) and conjunction (and, that, and that).

Both the every-sentences ("Every man who has a driving-license drives a car.") and the if-then sentences ("If a man has a driving-license then he drives a car.") can be used. The if-then sentences are more flexible in the way the verbs can refer to existing nouns via anaphoric references (pronouns, variables, and definite noun phrases). However, it is often the case that OWL cannot express this kind of argument sharing between verbs. Therefore, it is a good idea to only use every-sentences and avoid all kinds of anaphoric references to nouns occurring in the same sentence.

Every man is a human. (man ⊆ human) If there is a man then the man is a human. (man ⊆ human) Every professor is a scientist and is a teacher. (professor ⊆ scientist ∩ teacher) Everybody who is not a child is an adult. (owl:Thing ∩ ¬ child ⊆ adult)

Equality of classes has to be spelled out, there is no shorthand construction like OWL's EquivalentClasses.

Every carnivore is a meat-eater and every meat-eater is a carnivore.

Disjointness of classes can be expressed via ACE's negation which maps to OWL's ComplementOf.

Every man is not a woman. (man ⊆ ¬ woman) No man is a woman. (man ⊆ ¬ woman) Nothing is a man and is a woman. (owl:Thing ⊆ ¬ (man ∩ woman))

Transitive verbs and adjectives introduce the SomeValuesFrom restriction.

Every man who knows a publisher writes a book. (man ∩ ∃ know publisher ⊆ ∃ write book) Every man likes a dog or likes a cat. (man ⊆ (∃ like dog) ∪ (∃ like cat)) If there is a woman then she does not like a snake. (woman ⊆ ¬ ∃ like snake)

OWL's AllValuesFrom constraint

e.g. that carnivores eat only meat (if they eat at all),

can be expressed by double negation.

Let's say we want to express that carnivores and meat-eaters are equivalent

concepts (i.e. that carnivore = ∀ eat meat).

No carnivore eats something that is not a meat. Everybody that doesn't eat something that is not a meat is a carnivore.

There is also a shorter ACE syntax for some patterns of AllValuesFrom (i.e. where AllValuesFrom is on the right side of the subsumption sign).

Everything that a carnivore eats is a meat. (∃ inv(eat) carnivore ⊆ meat) Everything that is eaten by a carnivore is a meat. # the same using passive

Classes can also be described in terms of a property and its cardinality. (Note that the plural of `thing' will be mapped to owl:Thing.)

Every woman likes more than 2 things. (woman ⊆ >= 3 like owl:Thing) Every millionaire owns at least 2 cars. (millionaire ⊆ >= 2 own car)

Reflexive pronouns (`itself', `himself', `herself') can be used to describe (ir)reflexivity.

Every narcissist likes himself. No river flows-into itself.

Classes can also be described in terms of a property and its value that is either an individual or data-value. This corresponds to OWL's HasValue construct. For individual-valued properties, one must use a transitive verb (or adjective) with an object that is a proper name or a reference to an individual that has already been introduced.

Every man knows John. (man ⊆ ∃ know {John})

There is a woman who everybody likes. (w ∈ woman; owl:Thing ⊆ ∃ like {w})

John likes every dog. (dog ⊆ ∃ inv(like) {John})

Every dog is liked by John. # the same using passive

For data-valued properties, ACE makes use of the copula verb `is', a genitive construction (Saxon Genitive, possessive pronoun or an of-construct), a noun which expresses the property, and finally a number or a string. For example

Everybody whose age is 32 is a grown-up. If there is a man who lives-in Paris then the man's address is "Paris". For all water it is false that the temperature of the water is -1.

where the genitive construction is expressed by `whose', `man's', `of the water', the property is expressed by `age', `address', `temperature', and the data-value is `32', `"Paris"' and `-1'.

OWL properties correspond to ACE's verbs and transitive adjectives (e.g. `taller than').

A superproperty for a given property can be defined as:

Everybody who loves somebody likes him/her.

or in a more verbose manner:

If there is somebody X and X loves somebody Y then X likes Y.

Disjointness of properties can be declared by using negation.

Nobody who likes somebody hates him/her.

or more verbosely:

If somebody X likes somebody Y then it is false that X hates Y.

Property chaining is a complex mathematical concept that does not have a simple verbalization in natural language. E.g. the transitivity of a property is formulated in ACE in the following ways (different levels of syntactic compactness are provided):

If something X is taller than something Y and Y is taller than something Z

then X is taller than Z.

If something X is taller than something that is taller than something Y

then X is taller than Y.

To declare an inverse property of a property, two sentences are needed.

If something X is taller than something Y then Y is shorter than X. If something X is shorter than something Y then Y is taller than X.

The rest of the syntax that OWL provides for describing properties is just syntactic sugar, one can use the already described class relations, cardinality constraints and inverse properties instead.

Properties can have a domain and a range. The domain of a property can be expressed e.g. by

Everybody who writes something is a human.

The range of a property can be expressed by:

Everything that somebody writes is a book or is a paper. Everything that is written by somebody is a book or is a paper. # the same using passive

Properties can be functional and inverse functional. Functionality means that for a given subject, the object of the property (verb) is always the same. Inverse functionality means that for a given object the subject must always be the same. For functionality, one has to restrict the class owl:Thing to have at most one value for a given property (it is OK to have no values at all).

Everybody orders at most one thing. (owl:Thing ⊆ <= 1 order owl:Thing)

Inverse functional properties are expressed by switching the subject and the object of the verb.

Everything is something that at most one thing orders. (owl:Thing ⊆ <= 1 inv(order) owl:Thing) Everything is ordered by at most one thing. # using passive

Symmetric property is its own inverse. The various ACE syntaxes to express this are:

If somebody X loves somebody Y then Y loves X. Everybody who is loved by somebody loves him/her. Everybody who somebody loves loves him/her.

Equivalent properties are expressed by declaring the two properties to be superproperties of each other.

Everybody who hates somebody despises him/her. Everybody who despises somebody hates him/her.

User acceptance of the reasoning results obtained on the OWL level and perceived on the ACE level provides the basis for proving that the mapping from ACE to OWL is useful. Given the ACE text

John is a man. No man is a woman. John is a woman.

the reasoner will find an inconsistency because John has been asserted as a man and men have been described as disjoint from women.

Here is another example.

Every child is a man or is a woman. No child is a man. No child is a woman.

This text may seem strange, but it is not inconsistent, as far as OWL is concerned. All we have done, is constructed an empty class child, which is perfectly legal (one can say, though, that the class child is unsatisfiable). Only when we claim that there are elements (individuals) in this class, for instance by stating

John sees a child.

do we end up being inconsistent.

Reasoning about property restrictions finds inconsistency in:

Every man sees a dog. Nothing is a dog. John is a man.

Reasoning about properties of properties. The following text is consistent.

No dog likes a cat. Fido is a dog. It loves a cat.

But it becomes inconsistent if we add information about the relation between `like' and `love':

Everything that loves something likes it.

We can also reason about the domain and range of properties.

Everything that somebody writes is a book. Everybody that writes something is a human. John who is a man writes a paper. Every man is a human.

Inconsistency is caused when we now claim that:

No paper is a book.

Reasoning about cardinality, e.g. functional properties. Imagine a library policy saying that everybody can order only one item from the library, and that John places two orders.

Everybody orders at most one thing. John orders a book X and orders a book Y.

This text is consistent, namely because the reasoner sees nothing strange about taking X and Y to denote the same item (individual). Only when we state that:

X is not Y.

would it become inconsistent.

Reasoning about inverse functional properties is similar.

Everything is ordered by at most one thing. Mary orders a book X. Bill orders the book X. Mary is not Bill.

Reasoning about transitivity and HasValue will find the following text inconsistent.

If something X follows something that follows something Y then X follows Y. John follows Mary who follows Bill who follows John. No manager follows Mary. Bill is a manager.

Reasoning about inverse properties. In ACE, in many cases, one does not have to explicitly assert a named inverse property of a given property. One can simply use a passive verb to create an (unnamed) inverse property. An inconsistent text, containing an inverse property, can be constructed like this:

John likes Mary. Nobody is liked by John. # This statement would be redundant: #If somebody X likes somebody Y then Y is liked by X.

Reasoning about nominals (i.e. OWL's OneOf construct). The following text is inconsistent.

Every student is somebody who is John or who is Mary. Bill is a student who is not John and who is not Mary.

To learn ACE, check out the Attempto project website at http://attempto.ifi.uzh.ch/site/. The Attempto project provides tools for working with ACE, in particular, Attempto Parsing Engine (APE) can be used to convert ACE texts into Discourse Representation Structures and then to OWL.

APE is available under the LGPL license, but it can also be used through a REST webservice. For example, an OWL ontology that corresponds to the ACE text ``Every man is a human.'' is given by the URL

http://attempto.ifi.uzh.ch/ws/ape/apews.perl?text=Every+man+is+a+human.&solo=owlxml

The resulting ontology is represented in the XML Serialization syntax. For a Prolog-based serialization, use solo=owlfss.

To visualize and reason about the ontologies that APE generates, load the generated XML output into an ontology editor that supports OWL 2 (e.g. Protégé 4).

Kaarel Kaljurand (kaljurand@gmail.com), 2010-11-04